Journals

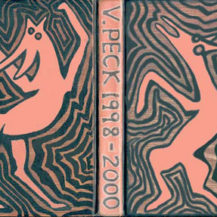

Finding a discarded book, I started using it as a journal/sketchbook. The original book was Natural Light by Ethel Gorham. When I was finished painting all the pages I painted over the cover. This altered book was exhibited in 2000, part of the show, The Book as Art: Artists’ Books in New England, Cambridge Art Assoc., Cambridge, MA.

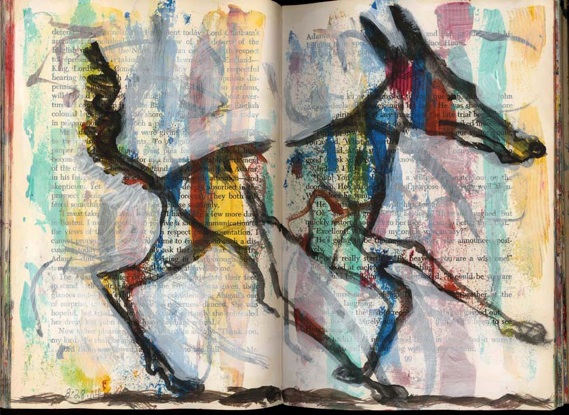

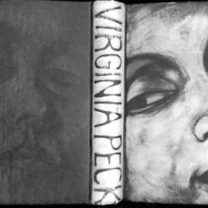

The second book I chose from the “library shed” at the town refuse and recycling center, was The French Lieutenant’s Woman, by John Fowles. I chose this book because the main character is a woman artist, and I had read it and enjoyed it years earlier, as well as other books by this author. Since I knew and liked the story, and because I had been an illustrator for 12 years, I was at first stymied by what to do. Should I illustrate the book or continue my technique of using it as a sketchbook, where my unconscious mark making led the way? Once I decided not to illustrate the story, my imagination felt set free to proceed, unlimited by the story, although, most probably, subliminally affected by it.

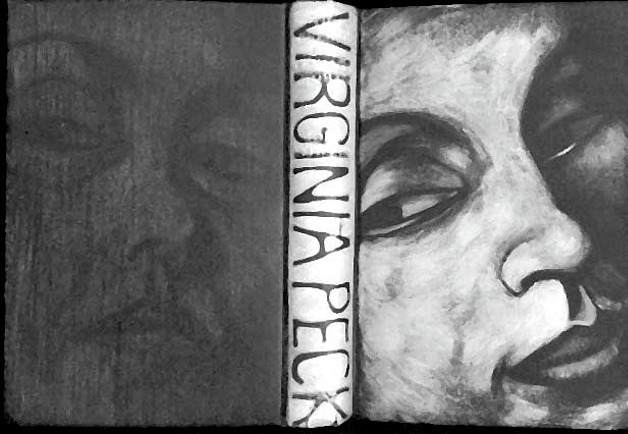

The 3rd Journal Sketchbook I chose was, Nicholas Wycoff’s The Braintree Mission, A Narrative of London and Boston 1770 – 1771. I admit that I chose it due to it’s fewer pages that wouldn’t take as long to complete. Because I had been invited to have a show of my Journal prints at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society & Institute, and because people had been encouraging me for years to make a book, I decided to create a book called Anima, A Visual Journal by Virginia Peck that was a selection of images from this third Journal. So I hired a book designer to help shepherd me through the process. It was a disaster. With only 3 months before the opening, the designer’s mother got sick and she had to spend weeks at a time in Florida, plus the chosen printing process dulled all the vibrant colors. It was a frustrating and painful learning experience. The best part, though, was that I was honored to have a famous author write the Foreword to Anima. Indra Sinha, who had been a 2007 Finalist for the Man Booker Prize in Literature for his book, Animal’s People, had discovered my Journals online a few years earlier, become a fan, and included me in artist interviews he was conducting. If you scroll down the page, you can read his wonderful writing, the Foreword to my book, Anima.

I recently started three new Journal Sketchbooks. I work in all three simultaneously. For Journal 4 I’m using the book Medicine Cards by Jamie Sams & David Carson. This book was given to me many years ago by a friend.

For Journal 5 Sketchbook I’m using The Secret, by Rhonda Byrne. When a friend was leaving San Miguel de Allende, she said I could go through her books and take any I wanted. I liked the small format of this book.

For Journal 6 I chose the book Imagine a Woman in Love with Herself by Patricia Lynn Reilly. This was another book that was offered to me by the friend as she was leaving town. I liked the title and the small format of the book and that the author writes and gives workshops about spirituality and creativity.

Sketchbook Journal Process by Virginia Peck

I first started painting in books in 1998, when I chose one from a huge pile that someone had put out on the sidewalk for collection. I had been toying with the idea of using a regular book as a sketchbook, so when I came across this pile of books, it felt very serendipitous. Like most of us who are trained as a child not to deface a book, I felt a little guilty at first, but the fact that it was being thrown away helped to assuage my conscience. I then found a ready supply of books at the town refuse and recycling center, with a “library shed” of discarded books. And through the years, often when they are moving or decluttering, friends have given me books or allowed me to scavenge their shelves.

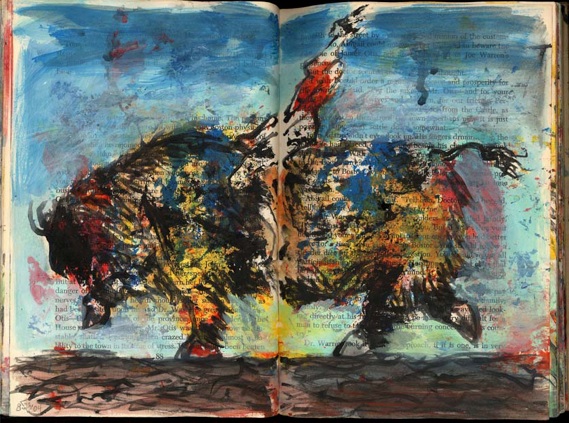

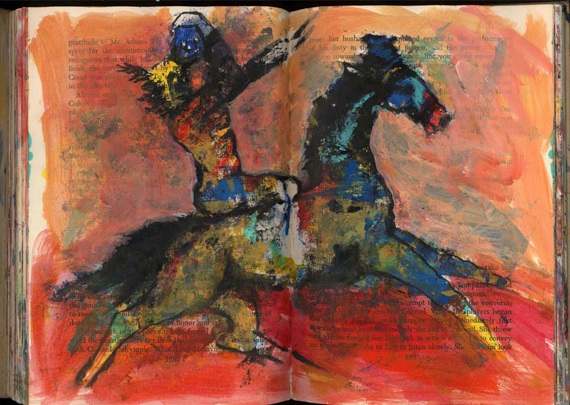

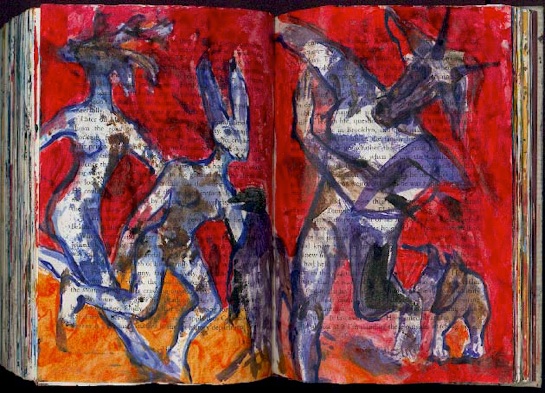

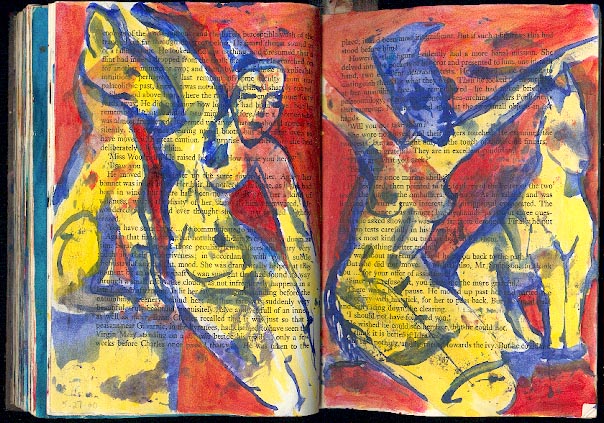

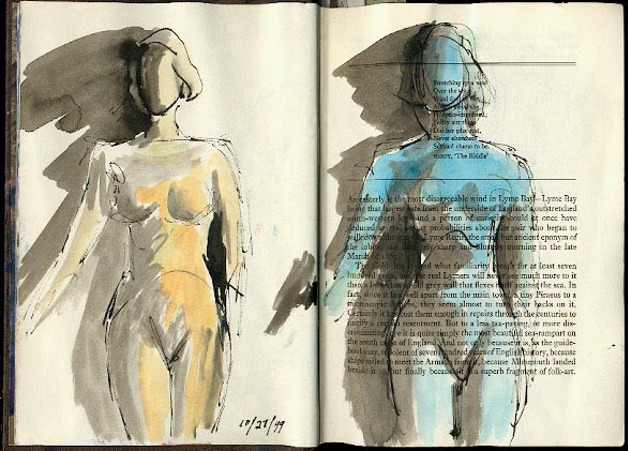

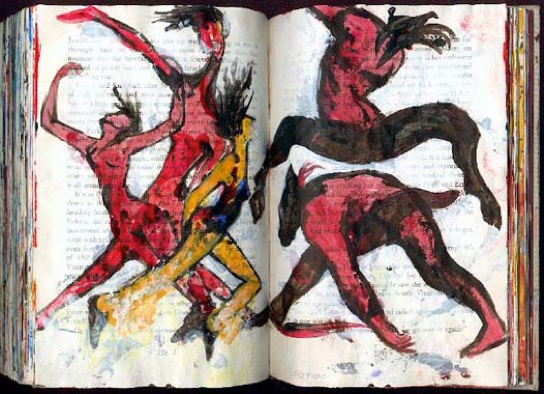

In most of the images in my journals, I have played with a similar technique that Leonardo Da Vinci used to spur his imagination. He would throw an oil-soaked rag at the wall and in the stain that it left, he would start to see whole battle scenes. I begin with the layer of text in a book, adding swipes of color, left hand, right hand, or with my eyes closed, so as not to influence what might come later. A rich layering is built comprised of colors and marks overlapping one another on the paper. This first creative encounter will then be put aside, sometimes for quite a while.

Later I’ll return, and rather than allowing my mind to rush in and impose preconceived notions on the page, I give my unconscious time to see what it can find. Gradually, I will see parts of images taking shape out of the interplay of text and paint. I draw out these dancing figures and creatures, connecting the missing parts, never knowing where the forms will take me or what the final composition will be. From this chaos of gestural movement, my imagination sees what is lurking there in the paint, moving just under the surface, waiting for liberation. Letting the paint lead the way, I find that this technique is endlessly creative, fun, and surprising for both myself and the viewer.

Much later, occasionally, I can see a relationship between the final image and something that was happening in my life at the time. There is a mysterious, sometimes joyful, often strange glimpse of another plane of awareness, portals into the archetypal, mythological or the underlying, partially hidden, current zeitgeist that the rational mind may only understand years later, or never. In some of these images, I now realize that my unconscious had been influenced, not only by mythological half-man, half-beast creatures in antique sculptures and paintings but also by seeing magazine photos from the 1970s of the decadent parties of the rich and infamous wearing stag-horned animal heads, devils, and other dark creature masks. And interesting that I was creating (uncovering/disclosing) a lot of these around the time of 9/11, the evilest act in modern times against the American people. Now I see that there was a soul level of knowing, beyond what my mind comprehended at the time. But aside from these prescient occurrences, what I love most is the process of discovering what is expectantly waiting there to be found and the sheer joy of bringing it into existence.

Foreword written by Indra Sinha

for Virginia Peck’s Journal Anima

Indra Sinha’s novel, Animal’s People, was a

Finalist for the 2007 Man Booker Prize and it was the

Winner of the 2008 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize:

Best Book from Europe & South Asia.

Once in a jumble sale, I found an old novel. Its cover was mostly torn away revealing a title page with a handwritten dedication, slowly dissolving in an English drizzle-mist. It was a wretched sight to anyone who loves books. All books are valuable. There is always something interesting about them. If not the text it might be an engraving, or the type, or the quaint old advertisements you sometimes find before the endpapers.

I picked up this damp, unloved novel, thinking I would save it, and to my astonishment found it was one of my own. The blue blurring lines had been written for a friend. Such humbling moments are no doubt good for us, but not too often. I still have that book. I’m looking at it as I write this, and thinking that such a miserable tome could have no kinder fate than to be picked up, not by its author, but by a stranger, a passerby with a rare and restless genius, who would give it new life as a ravishing work of art.

You’ll gather that I’m a fan. I admire – no, love – nay adore – Virginia Peck’s hand-painted Journals, but I don’t believe a word of her story.

Virginia says that one day, finding a discarded copy of Natural Light, a novel by Ethel Gorham, she was seized by the idea that she would take it home and use it as a sketchbook. Virginia had not read the novel and was not interested in trying to make images out of what was written on the page. Rather she would begin working by instinct, almost with eyes closed, waiting for what would come, and when shapes appeared in the paint, in the layers of colour and brushstrokes, she would work with them, and let them become whatever wanted to emerge.

Her first Journal quickly filled with marvelous images. A blue lady stares out at us with startled eyes. What is she seeing? Driftwood sculptures are heaped together, a ring of them like dancers, or a wood-henge washed in by the tide. Bacchantes abandon themselves to dance watched by a pair of still Pharoah hounds. A pensive youth, looking a lot like Raphael’s portrait of Agnolo Doni huddles next to an exotic tribal face. What is going on here?

I first saw these pictures as small images, neat rectangles on a web page. Even then they filled me with excitement. Inside were wonderful things, fizzing with life and energy, and so exhilarating to paint that Virginia found herself unable to wait for the pages to dry, and had to start working in a second book.

Journal II (John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman) seemed more reflective, but is no less brilliant. A mad tiger lifts its head and cries defiance, there’s an excellent frog and a zebra caught in a maelstrom of colour. Most of the pages are given to dancing couples and pairs of heads. Two nudes rest against a wall. I could swear that the one on the right is pointing a gun but her hand is empty.

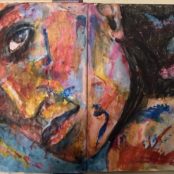

For her next trick, our illusionist chose Nicholas Wycoff’s The Braintree Mission, a 1957 first edition. (It’s me, not Virginia who cares about such details.) This became Journal III, the one you have in your hands. This is Virginia’s trickster journal, full of magical shapeshifting beings that are constantly transforming themselves.

Here is the Trickster Coyote of innumerable Indian legends. Here are imps and magicians, prancing spirit horses, a winged deer, a woman rodeo-riding a bison, a monkey woman riding a two-headed dragon. Turning the pages of this Journal is like watching a ceremonial spirit dance.

Was Virginia using these abandoned books as casual sketchbooks? – well it’s a good story but as I said I don’t believe a word of it. What she is doing is something darker, far more powerful, and dangerous. In the female figure clinging to the backs of wild beasts we see a woman and artist fighting to come to terms with the worst things in her life.

I first heard of Virginia through her famous series of Buddha portraits. To catch that perfect smile, to paint peace and silence with a brush is a remarkable achievement, requiring flawless control. Such control, as the Buddha himself taught, is gained only by grappling with one’s demons and learning to love them. A battle requires a battleground and where else do demons haunt but in imperfect things, despised and outcast, like unloved, unwanted books?

I was doing a series of interviews with artists and asked Virginia if I could include her. This led to one or two video calls across the ocean. I asked if she would hold up one of the Journals.

Looking through the computer screen, what I wanted more than anything was to reach through and take it in my hands.

Imagine the pleasure of holding one of those books, heavy with paint-encrusted pages that have slightly buckled and no longer lie flat, so that it doesn’t quite close, but bulges, giving you glimpses of what’s inside. Imagine the colours. The subjects. The textures. The feel of dried on paint. The crackle of a page as, very carefully, it is turned.

I love being a writer, but looking at Virginia’s painted Journals makes me want to give up words and be a painter.

Indra Sinha, Sussex, England